Atrial fibrillation (AFib) affects more than 3 million Americans and is the most common abnormal heart rhythm. AFib increases the risk of stroke, heart failure, death and can significantly impact the quality of life. In addition to treating the abnormal heart rhythm, treatment of atrial fibrillation involves stroke prevention.

After atrial fibrillation is diagnosed the risk of stroke is assessed and anticoagulation is recommended if risk factors are present. Oral anticoagulants are used in the treatment of atrial fibrillation because people with AFib are at increased risk of blood clots forming in the heart, especially within an area of the heart called the left atrial appendage. The type of anticoagulant therapy recommended will depend on if you have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation or have valvular heart disease that is causing your AFib.

Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation is not the only option to reduce risk of stroke. If the anticoagulant side effect of bleeding is not tolerable due to a person’s risk of bleeding, falls, or occupation/lifestyle that creates a higher risk for bleeding, a cardiac surgery to close the left atrial appendage is an option.

What is an Anticoagulant?

An anticoagulant is a medication that interferes with the body’s ability to produce blood clots. Anticoagulants are commonly known as ‘blood thinners’.

Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation is very common and most people with atrial fibrillation use long-term anticoagulation. Taking an oral anticoagulant decreases the risk of stroke associated with atrial fibrillation.

Oral anticoagulants are taken once or twice daily. Warfarin was once the only drug available for oral anticoagulation. While warfarin is very effective, taking it can be cumbersome because dose levels are affected by diet and medications and it requires frequent monitoring with blood tests. Newer oral anticoagulants are available which are also very effective for stroke risk reduction in nonvalvular AFib. They are not affected by diet and do not require routine blood tests for monitoring dose efficacy. However, they can be prohibitively expensive.

What Are the Benefits of Anticoagulation?

People with atrial fibrillation have a 5-6 times increased risk of stroke. Anticoagulation reduces the thromboembolic risk associated with atrial fibrillation. Thromboembolic means a clot (thrombus) forms in one area of the body and then travels to another area of the body (embolism).

In atrial fibrillation, thromboembolism occurs when a clot forms in the heart, enters into circulation and travels to the brain. AFib increases the risk of thromboembolism and, ultimately, stroke because the chaotic rhythm of atrial fibrillation causes blood to pool in the upper chambers of the heart. When blood pools it can coagulate and form blood clots. As the heart pumps, those blood clots can break free, enter into circulation and be taken to the brain. A blood clot in the brain reduces or blocks blood flow to that area of the brain and causes a stroke.

Anticoagulants help mitigate the risk of stroke in people with atrial fibrillation by making the blood clots less likely to form in the heart.

How Much Does Anticoagulation Reduce Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation?

Even though long-term anticoagulation is very effective at preventing strokes, it does not eliminate the risk of stroke. Anticoagulation for AFib is estimated to decrease the risk of stroke by 60-70%. If a person has a higher risk of stroke at baseline, the residual risk of stroke with anticoagulation will also be higher compared to someone who has a lower stroke risk.

A scoring system (CHA2DS2 VASc) is used to determine the stroke risk in a person with AFib. As the number of risk factors increase so does the annual risk of stroke. The risk calculator is used to assign for each of the various atrial fibrillation-related stroke risk factors. These risk factors include:

C – Congestive heart failure (1 point)

H – Hypertension or high blood pressure (1 point)

A2 – Age greater than 75 years (2 points)

D – Diabetes mellitus (1 point

S2 – History of stroke, transient ischemic attack (i.e. mini-stroke), or thromboembolism (2 points)

V – Coronary artery disease, heart attack or peripheral arterial disease (1 point)

A – Age between 65 and 74 years (1 point)

Sc – Female Sex (1 point)

If you have atrial fibrillation, your CHA2DS2 VASc score tells you your annual risk of having a stroke. You and your healthcare provider can use this information to determine if an anticoagulant is recommended and estimate how much benefit you will get from anticoagulation. Anticoagulation is recommended for men with a CHA2DS2 VASc score of 2 or greater and women with a score of 3 or greater.

Here are some examples of how the CHA2DS2 VASc score is used to help make treatment decisions for people with atrial fibrillation:

- Joe is a 76 year old male with AFib and high blood pressure. Joe had a heart attack 5 years ago. His CHA2DS2 VASc score is 4 (points for age, hypertension, heart attack). His annual risk of stroke is 4% and anticoagulation is recommended. Treatment with an oral anticoagulant will decrease his annual stroke risk to 1.4%.

- Anna is 68 years old. She has AFib and diabetes. She had a blood clot in her lungs when she was 40. Her CHA2DS2 VASc score is 5 (points for age, female sex, diabetes, and thromboembolism) and anticoagulation is recommended. Her annual stroke risk is 6.7%. Treatment with an oral anticoagulant will decrease this risk to 2.3%.

- Michael is 50 years old. He was recently diagnosed with atrial fibrillation. He has seasonal allergies and asthma. He has no stroke risk factors and his CHA2DS2 VASc score is 0. Anticoagulation is not recommended.

Previously, aspirin was considered to be an alternative to anticoagulation for people who were at lower risk for AFib related stroke or who could not tolerate an oral anticoagulant. However, aspirin has been found to have minimal effect on decreasing the stroke risk in atrial fibrillation and the American College of Cardiology guidelines on management of atrial fibrillation recommend against the use of aspirin for stroke risk reduction in people with atrial fibrillation. In the example of the patient Anna, anticoagulation decreases her annual stroke risk from 6.7% to 2.3%. If she were to take aspirin instead of an anticoagulant, her stroke risk would only be reduced to 5.4%. With this minimal stroke risk reduction, the risk of bleeding associated with aspirin therapy would outweigh the treatment benefit.

What is the Risk of Over Anticoagulation?

The primary risk of all anticoagulants is bleeding. Oral anticoagulants are considered high-risk medications because of this bleeding risk. Over anticoagulation can lead to a dangerously high risk of bleeding and death.

Bleeding risk is slightly higher with warfarin than with the newer oral anticoagulants such as Eliquis, Xarelto and Pradaxa. The overall risk of major bleeding is 2-5%. Examples of major bleeding events are:

- Intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding into the brain)

- Intraocular hemorrhage (bleeding in the eye that impairs vision)

- Bleeding that causes a significant amount of blood loss resulting in anemia

- Bleeding due to anticoagulation that requires hospitalization

The risk of minor bleeding with oral anticoagulants is about three times higher than major bleeding. Minor bleeding events have been shown to increase the risk of major bleeding events. The most common kinds of minor bleeding events on anticoagulation are:

- Nosebleeds

- Bleeding gums

- Blood in urine

- Heavy non-menstrual vaginal bleeding

- Gastrointestinal bleed with black or dark, tarry stools

- Excessive bruising

- Vomiting blood or something that looks like coffee grounds

Certain medications and foods can increase the risk of bleeding by changing the way the anticoagulant is metabolized by the body or can add to the anticoagulant effects of the blood thinner. If you take an anticoagulant, always ask your doctor before starting any new vitamins, herbal supplements or medications. Over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), naproxen (Aleve) and aspirin have an additive effect when taken with anticoagulation which can result in an increased risk of bleeding.

All anticoagulation carries with it the risk of serious and potentially fatal bleeding. Therefore, when deciding if a person should take an anticoagulant the risk of bleeding is always weighed against the benefits of anticoagulation. While the CHA2DS2 VASc score helps doctors assess the risk of stroke and guides anticoagulation recommendations, risk calculators are also used to assess bleeding risk. The HAS-BLED score is a tool that is commonly used to determine a person’s bleeding risk. Just like with the CHA2DS2 VASc score, the HAS-BLED score is calculated using points that are awarded for the presence of certain risk factors:

- Uncontrolled hypertension with the systolic blood pressure greater than 160 mmHg. Note: The systolic blood pressure is the top number on the blood pressure reading. (1 point)

- Liver disease (1 point)

- History of stroke (1 point)

- Prior major bleeding event or predisposition to bleeding (1 point)

- Unstable or frequently high INRs. Note: INR is a blood test that measures the effectiveness of warfarin. A high INR indicates that the blood is too thin. (1 point)

- Age greater than 65 years (1 point)

- Medication usage that increases bleeding risk (aspirin, clopidogrel, ibuprofen, naproxen, etc.) (1 point)

- Alcohol intake of more than 8 drinks per week. (1 point)

A HAS-BLED score of 4 or more is considered a high risk of bleeding. This means the risk of bleeding likely outweighs the benefits of anticoagulation and an alternative to anticoagulation should be considered.

If a person has atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation is contraindicated, there are cardiac surgery options, such as left atrial appendage occlusion, to decrease stroke risk. The left atrial appendage is a small pouch of tissue that protrudes off the upper left chamber of the heart (left atrium). It is estimated that over 90% of atrial fibrillation related strokes are caused by blood clots that originated in the left atrial appendage.

As discussed previously, the chaotic rhythm of atrial fibrillation can cause blood clot formation in the heart, especially in the left atrial appendage. If a clot leaves the left atrial appendage and enters the bloodstream it can travel from the heart to the brain where it can cause a stroke. If you have non-valvular atrial fibrillation and are unable to take an anticoagulant because of bleeding problems or an occupation or lifestyle that increases bleeding risk, closing the left atrial appendage effectively reduces stroke risk and eliminates the need for long-term anticoagulation.

When Do You Start Anticoagulation After a Stroke?

An ischemic stroke occurs when a blood clot blocks or reduces blood flow to an area of the brain and deprives that area of oxygen and nutrients. This causes brain tissue to die. Dead tissue is more likely to bleed. Studies have shown that starting an anticoagulant too soon after a stroke can cause bleeding in the brain. This is called hemorrhagic conversion and it can worsen the effects of the stroke or can be fatal.

If a person who was not already on anticoagulation presents to the hospital with an ischemic stroke, it is usually recommended to wait for at least 48 hours before starting anticoagulation. Aspirin use during this initial 48-hour period after an acute ischemic stroke has been shown to be beneficial. If a person with atrial fibrillation has an ischemic stroke while on anticoagulation, it is usually recommended that anticoagulation be continued without interruption.

Is Anticoagulant Therapy a Risk Factor for Stroke?

Anticoagulant therapy is a risk factor for bleeding in the brain and hemorrhagic stroke. While relatively uncommon, this is the most feared risk of chronic long-term anticoagulation and is often fatal. The risk of anticoagulation-related hemorrhagic stroke increases with age, high blood pressure, history of ischemic stroke, and higher dose anticoagulation. The risk of intracranial hemorrhage and other major bleeding events are the reason why your healthcare provider will use tools like the CHA2DS2 VASc and HAS-BLED scores to determine if anticoagulation is an appropriate part of your atrial fibrillation treatment plan.

An indirect way that anticoagulant therapy is a risk factor for stroke is that treatment with an anticoagulant indicates that a person has a higher risk of blood clots because the only reason a person is on an oral anticoagulant is to prevent blood clots. Whether anticoagulation is prescribed because of a person’s history of a clotting disorder, stroke, atrial fibrillation, or other condition that increases the risk of blood clots, an increased risk of clots usually translates to an increased risk of ischemic stroke.

What is the Safest Blood Thinner for AFib?

There are a number of anticoagulant drugs for reducing the risk of atrial fibrillation-related stroke. These include:

- Warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven). Warfarin has been used for atrial fibrillation for over 70 years. The anticoagulant effect of warfarin is monitored by a simple blood test called an INR. The typical INR goal for a person with AFib who is on warfarin is for the INR to be between 2-3. This is the level where blood is thin enough to prevent blood clots but not so thin that a person develops dangerous spontaneous bleeding. If the blood becomes too thin or a person develops bleeding there is an antidote for warfarin. Vitamin K can be given to reverse the effects of warfarin.

A factor that limits the safety and efficacy of warfarin is that its functioning is affected by a person’s diet and medications, it can be cumbersome to take because the dose may be different on different days of the weeks which increases the risk of medication dosing errors, and a person on warfarin has to get their blood checked at least every 4-6 weeks to make sure that the INR is ‘within range’, meaning that the warfarin dose is correct.

Warfarin is currently the only oral anticoagulation medication that is approved for stroke risk reduction in valvular atrial fibrillation.

- Novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). The newer anticoagulants (apixaban, rivaroxaban, diagabitran, and edoxaban) have been shown to have a lower risk of bleeding when compared to warfarin. While this technically makes them the safer anticoagulation option, they can be prohibitively expensive and reversal agents are not always available. If a person is unable to afford a medication, they are less likely to take it as directed. In this situation, people may try taking a twice-a-day medication only once a day in an effort to make the medication last longer. Unfortunately, this decreases the overall safety and efficacy of the blood thinner because an anticoagulant only works to prevent a stroke if it is taken as prescribed.

When the NOACs were first approved by the FDA, there was a lot of hesitancy to use them because of the lack of an antidote. Doctors and patients were concerned about what would happen if there was a major bleeding event and there was no way to reverse the medication. We have since learned that these medications wear off relatively quickly so that if a person who is taking a NOAC develops bleeding the NOAC is actually out of the system in less time than it takes Vitamin K to begin working to reverse warfarin. In addition, other treatment options and reversal agents for NOACs are now available to speed the process of returning the body to its normal clotting ability, if it were to be necessary.

- Heparin and low-molecular weight heparin (Lovenox). If a person with atrial fibrillation is at a very high risk of stroke and needs to stop oral anticoagulation in preparation for surgery, an intravenous anticoagulant like heparin or intramuscular anticoagulant like Lovenox may be used. These intravenous and intramuscular formulations act as a ‘bridge’ to protect a person with atrial fibrillation from stroke in the time leading up to surgery. However, they also leave the system very quickly so they do not significantly increase the risk of bleeding during surgery.

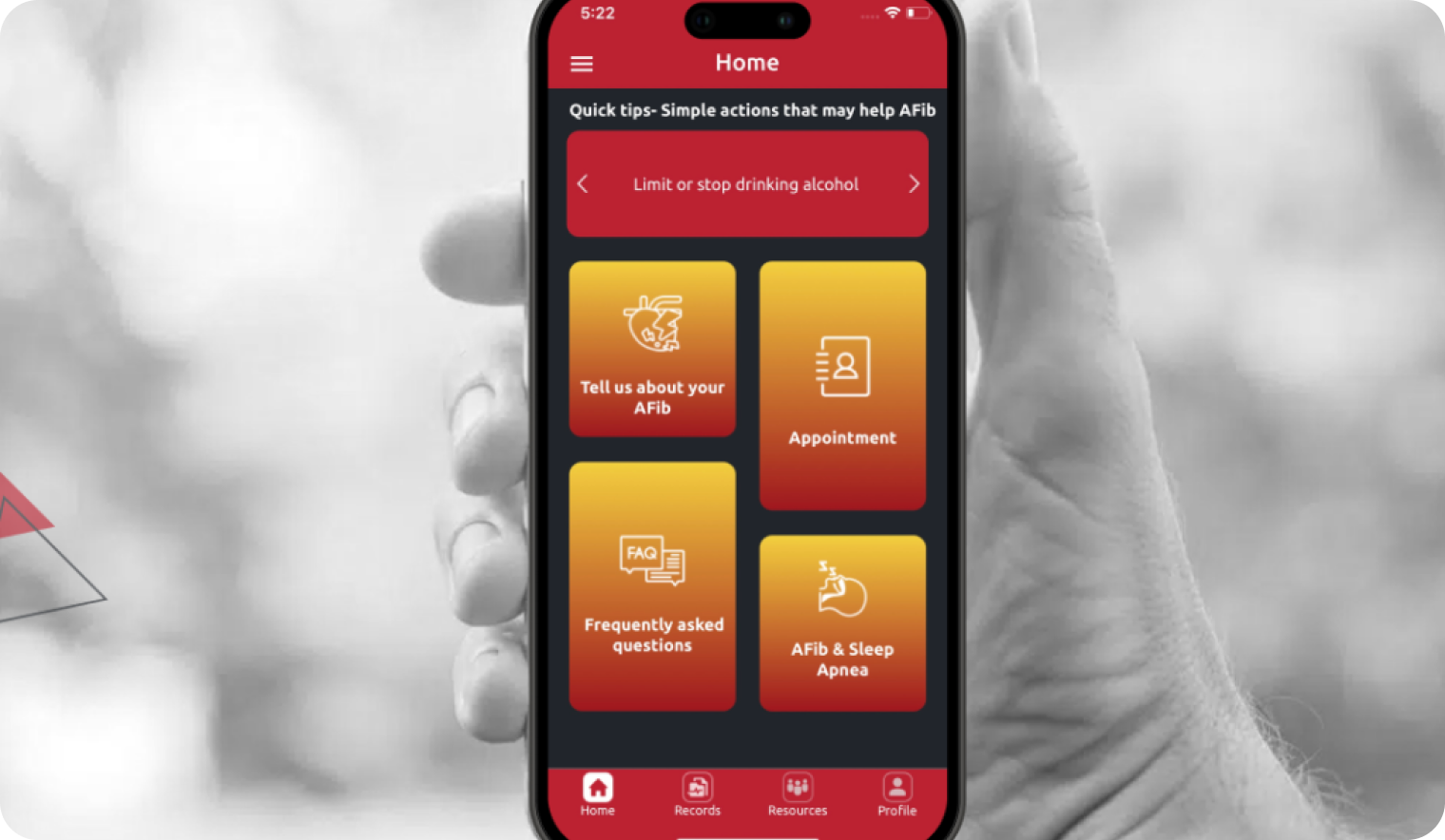

If you have atrial fibrillation, the decision of if you need anticoagulation and if so, which one can be complex. Take a list of anticoagulation questions and concerns with you to your appointment. If an anticoagulant is recommended, you and your healthcare provider will work together to choose the stroke prevention option that will work best for you and your lifestyle.